Part 1 of Community Stories: Music Journalism in Asia

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that music journalism is really, really niche in a tiny country like Singapore. With a small local music scene, you can probably count the number of homegrown music publications on one hand, Bandwagon and Hear65 included.

It also doesn’t help when so much of contemporary music criticism is still dominated by Western publications such as Pitchfork, NME, Rolling Stone, or even Internet music nerd Anthony Fantano, just to name a few. Many music journalists—myself included—often cite these “music bibles” as their rite of passage to the world of music criticism.

However, it would be myopic to presume that Singapore doesn’t have a rich history of music journalism, and to dismiss its cultural impact in relation to Western counterparts. Local music journalists of the ’80s and ’90s weren’t just individuals who had a lot to say about music; they were also organisers and musicians who served as key figures in the Singaporean underground.

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

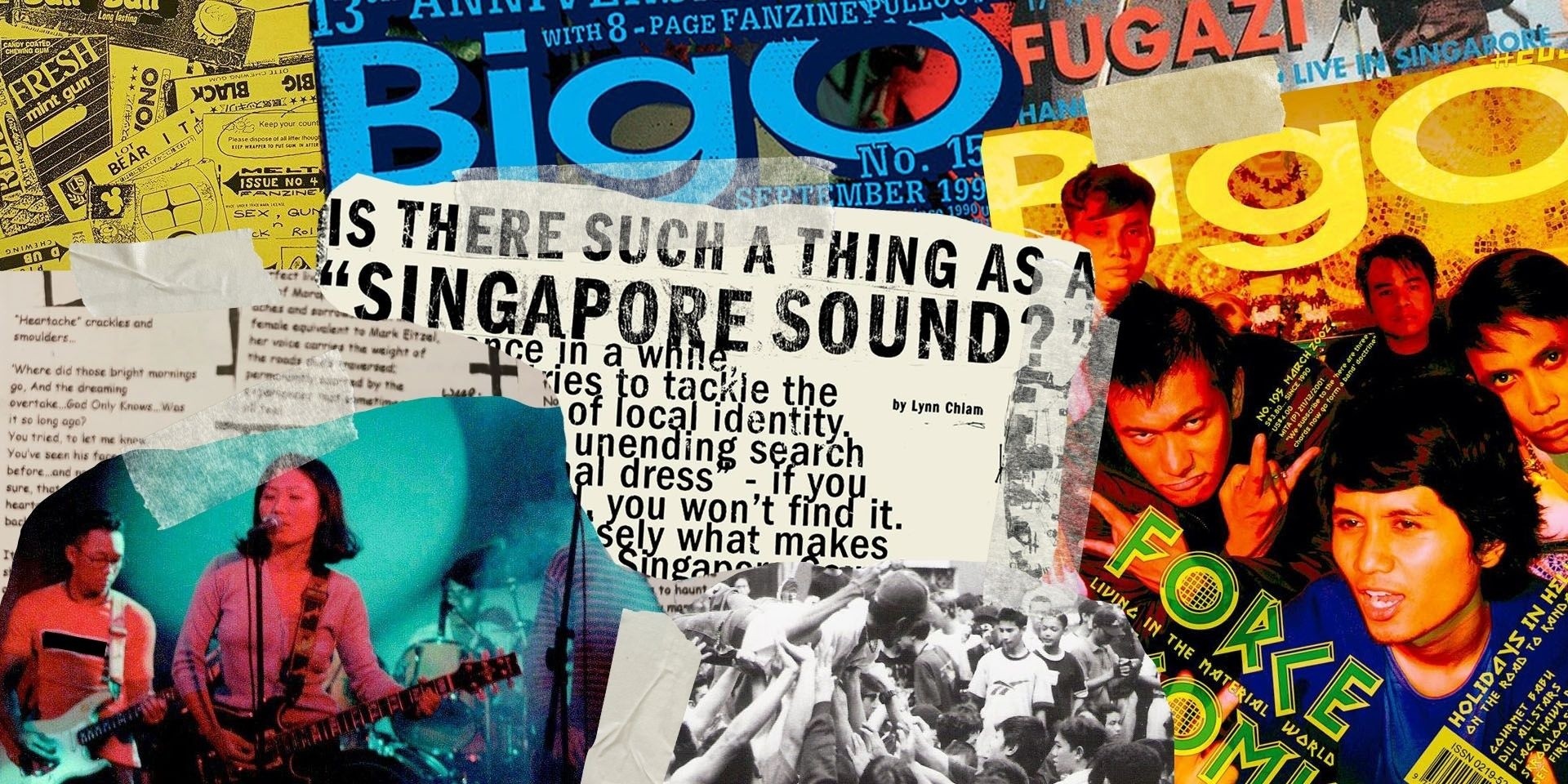

Take for example BigO Magazine, arguably the blueprint for generations of local indie publications to come. Formed in 1985 by Stephen Tan and brothers Michael and Philip Cheah, it documented the emergence of bona fide local independent music, with stalwarts like Zircon Lounge’s Chris Ho and The Oddfellows’ Patrick Chng also writing for the magazine. Beyond music news and reviews, BigO also organised gigs and released cassette compilations, quickly cementing itself as one of the few DIY institutions in the country.

It was a cultural epicentre not just for writers, but other creatives like designers, photographers, and filmmakers, all of whom did not operate in silos. Tirelessly championing local talent for almost two decades, the hallowed publication was more than just a storyteller of local music history, but an organic space for capacity building and creative exchange.

Credit: Roxy Records & Trading/Facebook

Credit: Roxy Records & Trading/Facebook

For newer generations of music fans who didn’t live through the era of DIY fanzines and illegal punk gigs, it might be harder to grasp the impact of these early music publications in a landscape that has largely shifted online. Today, with the decline in print, most music publications have gone digital, both mainstream and indie. Players like Big Duck Music, Life In Arpeggio, and Nevermind Magazine have now assumed BigO’s mantle, and the Internet has made music journalism more accessible than ever.

Yet, despite this increase in accessibility, it seems that music journalism as a craft remains largely amorphous in Singapore. What does good music criticism entail in a local context? Who exactly were the people chronicling the stories of the Singaporean underground, and how did they lay the foundations for our music community today?

In the first of a four-part series titled Community Stories: Music Journalism In Asia, Bandwagon attempts to answer these questions by speaking to four individuals about their involvement with early Singaporean indie publications.

How did you get started in music journalism, and how long have you been doing this for?

Eddino Abdul Hadi, music correspondent for The Straits Times: The interest started when I was very young. My parents had a lot of newspapers and magazines around the house, and the radio was always playing music. I used to hang around bookstores and read music magazines like Rolling Stone and Spin, and later discovered BigO, which stood out because it was local.

Then I got into the local and regional independent music scenes, which had a thriving zine culture. I worked on a couple of zines covering local and regional punk and indie scenes with friends when I was a teenager in the ’90s. That was probably my first attempt at music journalism. I studied mass communication in school and later graduated with a degree in journalism. I’ve also been playing music and going to gigs since my early teens, so music journalism was pretty much combining the two things I loved doing.

In 1999, the BigO editors invited me to write for them. I started by reviewing CDs, and then moved on to interviewing and doing profiles on local bands. This was done on the side; I had another full-time job as a copywriter at a graphic design firm at the time. Writing for BigO was kind of voluntary, and I didn’t get paid, but it was a great opportunity to hone my chops as a music journalist and delve deeper into local music.

In 2007, I joined The Straits Times as a music journalist, and I’m still doing it today.

Robin Chua, DJ: I didn’t really think of becoming a music journo right in the beginning. All I know is I wanted to share my love for music, and back then the only way was to write about it. So, I started writing when I was involved with my first fanzine, Melt. That was probably during the early ’90s, from mid-1990 to early 1991 onwards.

Credit: Robin Chua

Credit: Robin Chua

Melt was started by me and my good friend, George Chua. Inspired by British music mags like Sounds, Melody Maker, Volume, as well as BigO, we wanted Melt to cover the type of music we loved, which was indie, alternative, and the local underground music scene. We did about three issues officially; the fourth one was completed, but it didn’t get released due to reasons I can’t recall now.

After that, I learnt as I went along, and I still find myself writing about music here and there, be it one-off articles for JUICE Singapore, or for my own social media.

View this post on Instagram

Redmund Law, educator: It started when I was 19 and bored in national service. I was a reader of BigO Magazine and for the hell of it, I wrote to the editor and asked if I could write for them. It was out of my love for music and the youthful belief that I could do anything. This was in 1990, so I have been writing about music on-and-off for 31 years.

After BigO, I did occasional album reviews for MTV Asia in the late ’90s and some local magazines. It was never meant to be my job, and more as a hobby. That hobby extended into the 2000s, where I did a fanzine called Now You’re Just Being Ridiculous for indie music I loved then with a group of friends.

Credit: Redmund Law

Credit: Redmund Law

It was an entirely DIY thing where we handmade the zine and distributed it when we had our occasional ‘Indiepop Nites’ at whichever club or pub that would let us have the place for a Saturday night.

Credit: Redmund Law

Credit: Redmund Law

Little Ong, creative director at fFurious: I revamped BigO Magazine for my final year graphic design project at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in 1996 with the blessings of the editors. Later that year, I got a call from them asking if I was interested in designing the November 1996 cover, which I did for six years until their final issue in October 2002.

By then, I had formed my creative agency, fFurious, where my partners Joanne and Melvyn also started contributing to the cover designs. Other than the covers, I would design editorials when there was a local band story; I also shot local band portraits and gigs.

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

What’s one piece that you’re the most proud of? Tell us more about it.

EAH: I’m proud of every single article I write about the talents in the local music scene, because who else but people living in Singapore is going to write about Singaporean music?

I do enjoy interviewing or writing about the biggest music acts in the world, whether it’s Coldplay or Taylor Swift, but covering local music is pretty special to me because I identify with it more.

RC: Without a doubt, the best issue of Melt was Issue #4 (which was actually Issue #3, but we just wanted to fool around and make folks wonder if they missed out on an issue). We had a free cassette with five different titles from Mute Records, including Inspiral Carpets to Renegade Soundwave. We also had stickers of Teenage Fanclub’s Bandwagonesque, and the content was probably our best too. Shout out to Joe Ng (of Mee Pok Man fame) who got us the free tapes and stickers when he was working for the music label BMG back then.

RL: Being young, I rarely did major features for BigO, but there were times when I was allowed to interview international artists like Tears for Fears and 808 State when they came here to play a show at Zouk.

Credit: 808 State

Credit: 808 State

To be honest, there isn’t anything that stands out for me because I gravitate towards doing reviews, which I love. I suppose it would be the fanzine we did, even though it was an extremely niche and obscure thing that we made probably between 20 to 30 copies per issue.

Credit: Redmund Law

Credit: Redmund Law

LO: That might be Issue #151 in May 1999 of Humpback Oak. They were a band that I admired, but I didn’t know the members personally then, so it was exciting to shoot them and design their editorials.

I suggested meeting the band in Little India—an area that I grew up in—because I thought it had a gritty soulfulness that would make a good backdrop for their portraits. While the band consisted of four members, only three turned up as one of them was studying overseas. Conceptually, that would have been awkward to portray, but because the story was to mark the release of their sophomore album SideASideB—where they departed from their usual acoustic folk style to include experimental studio effects—I saw the opportunity to experiment with the visuals creatively as well.

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

The design also marked a departure for me stylistically. I shifted from a raw, grungy style (inspired by David Carson of Ray Gun) to a more 4AD, Vaughan Oliver-esque design that I’d also liked a lot then. The digital imaging and experimental typography were more subdued but still present, and this stylistically mirrored the nuances in SideASideB, where unexpected sounds surprised the listener.

What kind of resources were available for aspiring music journalists in the past, and were there any collectives or groups for you all to network?

EAH: In the mid-1990s, we had the Internet, but the information that you can find isn’t as extensive as it is today. There was certainly no social media yet. So, you can search for articles online and send emails, but there was also a lot of scouring for information the old-school way through books, magazines, zines, newspapers, and of course, by asking around.

When I was doing zines, there was a lot of communication through post. We connected with other DIY scenes in countries like Malaysia, so we would send each other letters or exchange zines via mail. I remember doing a lot of interviews via post too! You mail over the questions, and the interviewees would reply back with a letter and photographs. When I started interviewing bands for BigO in the late 1990s to early 2000s, it was all face-to-face, so I don’t remember doing any interviews through email or any other modes of online communication.

On Oddfellows, Zircon Lounges and Stompin' Grounds: Singapore's Rock Music

I also made sure to go to as many gigs as I could back then, because it was there that you met other people in the music scene: the bands, gig organisers, and fans. There was a lot of on-the-ground work; you build up your network by physically meeting people.

Credit: Ben Harrison

Credit: Ben Harrison

RC: As far as resources go, the main source of information would be the public libraries. If you’re rich enough, or if you know people, then it would be books or magazines from their private collections. For many of us starting out, we would also read magazines from bookstores like MPH or Times. Our days would be spent there reading and remembering as much information that our brains can take.

I didn’t really know of any collectives for journalists back then. For me, it’s more about meeting like-minded folks at local gigs. Sometimes, it’s through mutual friends’ introductions that we get to know people. I only got to know more music writers when I started writing for BigO.

Credit: Reynold Godwin Pereira/Facebook

Credit: Reynold Godwin Pereira/Facebook

RL: For resources, whatever music magazine you could get your hands on. I grew up in the ’80s and devoured pop music magazines from Britain, particularly Smash Hits. Back then, they had a certain British wit that probably most informs my own style. In the 1990s and 2000s, music megastores like HMV and Tower Records also had magazines and books that further exposed me to how other music writers expressed themselves.

As for networks, BigO was the cultural centre for most of us in the late ’80s and early ’90s. It was both a formal and informal collective that grew out of writing for BigO. Over time, the same few faces kept popping up, and even after most of us stopped writing for the magazine, it was something that helped tie us together. I still have friends from those days, and BigO served as an invisible network linking all of us over these 30 years.

Credit: Martyn See/Facebook

Credit: Martyn See/Facebook

LO: I learnt about indie music through magazines like BigO, NME, Ray Gun, The Face, and Q Magazine. There was also CMJ New Music Monthly that came with a free CD with every issue. Later on, with the advent of the Internet, music blogs and sites like Pitchfork became de rigueur for reading about music.

Credit: CMJ Holdings Corp

Credit: CMJ Holdings Corp

The music journalism scene is quite small and tight-knit, and many of us are friends with one another. Are there any individuals whom you’d like to give a shoutout to?

EAH: The BigO editors Philip and Michael Cheah, as well as Stephen Tan, who gave me my first opportunity to get into music journalism. And as mentioned, Chris Ho, whose music columns I devoured when I was younger.

I’m also really glad that there are so many platforms for local music writers that have emerged in the last decade or so: Bandwagon, Hear65, Big Duck Music, NME Asia, just to name a few. It’s a healthy sign that the Singapore music scene on the whole is never static, and is constantly evolving.

RC: Of course! He’s none other than my good friend, Redmund Law. These days he writes about music and the records he’s into on his Instagram account @redrimbaud.

View this post on Instagram

Funnily, we were both writers for BigO back then, but we didn’t get to know each other until years later after we were involved with the So Happy: 50 Years of Singapore Rock exhibition at The Substation organised by Little Ong and his fFurious team.

LO: Yo Eddino!

Do you feel that building community among music journalists in Singapore is important?

EAH: Of course! The work of music journalists does not exist in a vacuum. No matter which platform we’re writing for, I’d like to think that we are all serving the same people—the bigger community of music lovers, artists, and everyone else who make up the scene.

Pre-pandemic times, you would always end up meeting other music journalists at gigs and press events, so there were always a lot of opportunities to connect with others in the same field. These days, you’re probably more likely to do so via Zoom events.

View this post on Instagram

RC: Yes, because like any other creative practice, having a community is crucial in the exchange of ideas. As much as writing can be a very solitary thing, no writer should be left alone without any support.

RL: As mentioned above, it was a good thing to have that community. However, we were more than just writers who hung out together. It was ultimately the music that brought us together. We certainly did not exchange notes about writing.

A pictorial guide to the raw energy of Singapore's underground hardcore punk scene in the 1990s

In your words, what makes for good-quality music journalism? Do you feel that this exists in Singapore?

EAH: Yes, I’d like to think that good-quality music journalism exists in Singapore, although I believe that it will always get better as the quality of young writers have improved tremendously over the years.

There are a lot of things that encompass good journalism. For example, sourcing and writing stories that don’t just provide value to the readers, but also accurately reflect the music community and industry. Another aspect of music journalism is also the ability to give quality criticism.

RC: Although I think we have a few good-quality music journos here in Singapore, the majority of local writers tend to be too safe with their articles, or they are on the fence with no striking opinions of their own.

Either they are too afraid to speak their minds, lest they offend readers, or they merely recycle what others have written. A good music piece should not only be bold and striking, but it should also be relevant to your audience, educating them if need be—but without talking down to them. Lastly, be witty, so that you can get your point across in an entertaining way. I feel that humour is sorely lacking with most music writers here.

View this post on Instagram

RL: I’m not sure I can answer that as I will admit to being fairly disconnected from local music journalism today. Maybe because at my age, it’s harder to get into newer music now, so I rarely read about local music.

If I had to say what I believe is good music journalism, then I think it is being able to not just write about the music you hear, but relating the music emotionally to your readers. It comes back to the ability to connect with people.

LO: I enjoy reading about musicians beyond a write-up about their recent releases. I miss the in-depth articles in BigO where it’s as if the journalist and the musician were old friends catching up and reminiscing about old times.

In praise of FluxUs and friendship: Yuen Chee Wai on the now-defunct Singapore experimental music store and his 2018 album with Lasse Marhaug

What do you think can be done to push the potential of local music journalism?

EAH: I think that there could be more programmes similar to Esplanade’s Baybeats Budding Writers Programme, which I have been fortunate to be part of [as a mentor]. From my experience, the exchange of knowledge goes both ways, and I’d like to think that I learn as much from the mentees as they do from me. Having more established writers provide guidance to those keen on music journalism can only be good for local music writing.

View this post on Instagram

RC: In this age where everyone’s doing their own thing and operating within their own cliques, it can be quite a challenge to do that. Perhaps instead of pushing the potential of local writers, we also need to educate and grow the audience. You can have all the best writers doing their thing, but if there’s no growth in the audience and readership, it’s going nowhere.

RL: I’m not sure I have an answer to that. It probably depends on what you mean by “push the potential”. If the idea is to get local music writers to have a bigger audience not just domestically, then I suppose my answer is to be less parochial in the writing process. If you only think that you’re writing for people in Singapore, then I suppose that’s something that will likely limit your writing. But honestly, I don’t think I’m in a position to say what more can be done.

LO: Honestly, I don’t know where to read about the local bands that I like anymore. Perhaps it doesn’t exist. So, providing the platform and the space for lengthier stories would be great. Also, ensuring that journalists are paid a fair wage for their work will keep things respectable, and encourages effort for better stories to be told.

Credit: Martyn See/Facebook

Credit: Martyn See/Facebook

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers who may not know where to start?

EAH: The biggest lesson is to know who you are writing for, and to always know your audience. My favourite takeaway that I learnt from senior journalists is to always remember that you are not writing for yourself, you are not writing for your editors, but you are writing for your readers.

So no matter which platform you are writing for, take the time to learn who their audiences are, and understand how your work can bring value to them. Each platform—whether it's a national newspaper, a zine, or an online publication—will have their own distinct audience.

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

Credit: Little Ong/Facebook

RC: Familiarise yourself with music history and writings of the past, and develop your own style from there. Be real to yourself and what you believe in. Get to know other writers to develop and exchange ideas. These days, it’s easy to start and do your own thing. Just go forth and step out in faith! You will learn more as you go along. And most importantly, enjoy the journey.

Credit: Robin Chua

Credit: Robin Chua

RL: Have an open ear and mind to music. Write about what you love to hear. Have the heart to genuinely share what you love. I hate writing negative reviews, that’s why I rarely or never do it. If you want to be a music writer, you can’t not immerse yourself in music. The more you listen, the more you’ll be able to know what different types of music sound like, and the better you will be at articulating the music.

View this post on Instagram

If you really want to write, nothing will stop you even if nobody wants to hire you. Personally, I don’t know if I’m a good writer, but that doesn’t stop me from sharing my writing online now. Sure, I don’t make any money from what I do, but maybe that makes it all the more better. So to sum up: just keep writing.

This is part of the Community Stories: Music Journalism In Asia series that celebrates Bandwagon’s 10th anniversary and showcases local and regional music media championing Asian music.

Like what you read? Show our writer some love!

-